There's that joke that haunts every American attempting to expand h/er borders beyond the narrow continent:

There's that joke that haunts every American attempting to expand h/er borders beyond the narrow continent: Q: What do you call someone who speaks two languages?

A: Bilingual

Q: Three languages?

A: Trilingual

Q: One?

A: American.

Hardly encouraging when living within these borders and attempting to break the stereotype. Still, how often do I see this stereotype confirmed in the attitudes of most members in this society, even those who'd I expect otherwise. It is far too convenient to remain monolingual on this island... er, wait, we have neighbors to the north and south, and might boast of the most diverse communities--at least on the coasts, that is.

While English is the unofficial language of this nation, somehow we fear that learning a little of another language might topple this lingua domināns. Though this fear may be a bit unwarranted, I expect. No matter how hard we try to preserve English, it continues to be the global language most often learned as a second/other/foreign language in other countries. Experts suspect that before too long the number of non-native (proficient) English speakers in the world will trump the native English speakers. Before taking a collective sigh, all you linguistic imperialists, let us consider what this says about language ownership, representation, and how this corresponds to outdated nationhood identities, in general. Sure, we are clan creatures by nature and consequently need to latch on to that which distinguishes us from the other. But perhaps we might consider softening our grip on something so fluid as language. As a teacher, I understand the desire to try to keep English in place with a prescriptive grammar. But who really owns it anyway? The French and their ministry provide a definitive answer to this, believing that the one crucial way to preserve the culture is to preserve the language. I suppose every nation needs a narrative to highlight the lines of demarcation.

I don't know whether I agree entirely with the French on this point, but it seems far less vulgar coming from a country that embraces other languages more freely (or do they?). European countries may consider it a matter of political and economic survival, or simply, on a personal level, a reality that one is faced with on a daily basis: I am surrounded by other languages; I must conform. For those who remain monolingual, bilingualism is often viewed as a commodity, a sum of two languages, and, with some strange, vague way, that which is obtained along with an official certificate somewhere denoting fluency. There is little thought on the ever-present struggle: finding the vocabulary, the ideational, imaginative, or interpersonal functions; there is the constant battle for proficiency in every domain (writing, reading, speaking, and listening); and, of course, there is the fight to be authentic (i.e., correct). There is never enough with language, only a sense of adequate, and even that can topple.

Anyone who has attempted really learning a language beyond a college semester or two knows that second language competence is more than mere spewing of polished phrases to impress your friends. I cringe when a friend remarks at my ability to say a few phrases in Japanese. They express amazement at my ability to, say order when at an authentic restaurant. I can only imagine they have this false sense of what it means to be bilingual. They see the end, but do not fathom the process. There is no end, only struggle.

wait, there's more...

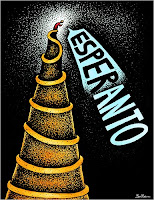

Image source: From Babel to Esperanto (Ben Heine)

1 comment:

I'm way late getting here, E, but I have to note that you're multi-culturalism is showing…

It's all about who is dominant, be it the Greeks, the Romans, the British, or the Americans. That's what creates a lingua franca.

And those who happen to be in the dominant group don't feel a need to learn the languages of others: that gradient works in only one direction: the desire to function in the dominant world drives speakers of the non-dominant language to learn the dominant language, because a need has been created.

English speakers, whether native or second-language learners, have the access, and have for the last couple of centuries, just as Greek speakers, and Roman speakers had in the past. I for one had nothing to do with being born into the dominant language group. It's just a fact of my existence, and I don't feel any guilt about it. If I learn a language, it will be largely for intellectual satisfaction, though I do see the moderate Spanish I know as being a pretty practical skill in this part of North America.

If a language is alive, it is changing, but we can still hold the prescriptive line, because standard use has much more to do with the basic grammar (grammar in the large sense) than it does with stylistics, which change each generation. Just watch some old B&W movies from the thirties for some examples.

Americans will learn Chinese when Chinese economic, political, and culture influences begin to eclipse the American, and no sooner. Then we'll feel the pressure, and it will be a natural process, just as it has been in the past.

Have a great summer!

Post a Comment